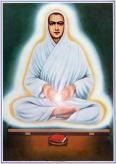

Ramalinga

For him God is a Light of Grace and compassion is the single step for realization

Ramalinga was born on October 5 in Marudur,15 km. north-west of Chidambaram, shrine of the Dancing Siva (Nataraja) in Tamil Nadu. His father, Ramaiah Pillai, of Saiva faith and belonging to the Vellala community, was village accountant and teacher. His mother, Chinnammai, belonged to Chinnakavanam, near Ponneri, in Chengelpet District, near Madras.

Legend has it that his birth and mission were prophesied by a Saivite saint who visited the house.

When Ramalinga was six months old, his father died, and his mother moved to her village, Ponneri. It is said that when he was five months old, his father took him to Chidambaram, and that Ramalinga, as a baby, had a vision of the 'secret' of Chidambaram, where the vacant space, shown behind a screen that is drawn aside, symbolises the formless God.

|

Early Childhood

Within a year (1824), Ramalinga's mother moved to Madras to join her eldest son, Sabapathy, a scholar of repute who made a living there by giving religious discourses.

When Ramalinga was five, his brother started teaching him. But Ramalinga was indifferent and spent his time day-dreaming. He used to play truant, wandering in the streets and sauntering in the corridors of the Kandaswamy Temple nearby, all through the day. Unable to control him, Sabapathy Pillai put him in charge of a Tamil savant, Sabapathy Mudaliar of Kanchipuram, who had been his own teacher. The savant proved equally ineffective.

Discovering that his boy-pupil was already drawing audiences in the temple with his talks and songs, he gave up the task.

However, Parvati, Sabapathy's wife, graciously prevailed upon him at last to please his brother and to take to his studies seriously He promised, requesting, however, that he might be provided with a room on the second floor where he could pursue his studies on his own. The request was granted. The truant returned home, and much to the satisfaction of his brother, never left the house or even the room where he remained shut all through the day.

Later Childhood

Ramalinga set a mirror against the wall, and set in front of it a naked flame--a wick burning in oil. With these as aid to concentration, he meditated. These were the same aids that he set, forty years later, in the prayer hall of the Temple of Pure Truth that he built in Vadalur. Identifying the Common Universal Soul symbolically with the flame, and the mirror as one's self wherein the flame is reflected, one strives to make one's mind pure

like an untarnished mirror, in order to have the Universal Soul reflected well within oneself.

And thus, says Ramalinga, is born the realisation of the Universal Soul, and with it, universal love and compassion for all creatures, seeing that it is the same flame which is reflected in all beings in varying degrees according to their development.

He started composing songs even at this age, or perhaps earlier, as he himself says to his Lord:

Little grown in body and less in mind,

little feet romping in the street,

I made songs, whom You made to sing,

You taking from formlessness...

It is stated (and Ramalinga himself says so in a poem) that, at the age of nine, he saw a vision of Lord Muruga of Thanihai in the mirror. In this room, untaught by anybody, he apparently acquired his learning by himself. For this he offers thanks to God in several of his poems, for example in the following:

Effulgent Flame of Grace that lit in me

Intelligence to know untaught...

The first song that he sang was before he was nine years old, and it was about the Lord Shanmuga or Muruga of Kandaswamy Temple. It was a series of 31 verses.

From Nine to Twelve

Substituting one day for the girl who used to read the religious texts from palm-leaf scripts for the discourses of Sabapathy, Ramalinga rendered them so soulfully that the audience thereafter insisted that only he should recite the hymns.

One day Sabapathy, who had a discourse scheduled in the house of a patron, Somu Chettiar, was ill. He sent Ramalinga to the patron's house to inform him accordingly. When Ramalinga went there, the audience had already gathered, and one among them suggested that Ramalinga might substitute for his brother.

Ramalinga spoke. The theme was the life of the hallowed saint-singer, Tirujnana Sambandar (Sambandar of Inborn Wisdom), whom Ramalinga had made his ideal. Without notes, without palm- leaf scripts, Ramalinga spoke. A flood of inspired eloquence flowed from him.

This was the first talk that he, coming out of the loneliness of his closed room, gave. He won over his listeners completely. Then on, they wanted Ramalinga to conduct all the discourses, and not his brother. Sabapathy agreed gracefully, turning to audiences elsewhere.

Ramalinga had a visitation of Divine Grace at the age of nine (1832). He himself narrates this in one of his poems:

Just Dispenser of men's needs and meeds,

O Self-Effulgent Light, Glowing

Central Flame of Cosmos,

Guide of my life who possessed me when

I was nine, and led me to

Your Kingdom and made It mine,

In You I have lost the need to

know what 1 need.

The divine fellowship, however, did not resolve his spiritual struggles which he dates from the age of 12:

The plight that has been mine from

twelve to this day,

O Lord, will suffice to melt a mountain.

The plight that has been this wretch's,

O Lord, from twice six years to

this day may melt dead steel.

He recoiled from the need of eating, as he confides to his Lord:

He had no desire for money. Whatever money was given to him for his discourses, he threw away in wells or ponds or tanks, or sometimes back at the donor.

His patrons, coming to know that he threw away the money given to him, used subsequently to give the money to his brother and not to him:

Likewise he discarded, even at this early age, all trappings of belief and faith, and stuck to his concept of God as Luminous Pure Intelligence.

Songs and Miracles

At the age of 12, when his spiritual struggles began, Ramalinga began to frequent the shrine of Tiruvottriyur, 10 km. north of Madras, and to worship Lord Tyagaraja (the ascetic aspect of Siva) and Goddess Vadivudai Ammai in the temple there.

For 23 years, all through his stay in Madras, Ramalinga used to escape from the city, and go daily to Tiruvottriyur on foot, composing poems and songs on Lord Tyagaraja. Tired out, he would often spend the night there, sleeping in the open. He used to visit also Tiruttanihai (the shrine of Muruga), Tiruvalidayam and Tirumullaivayil. He also visited Tiruvallur and Tirukannamangai, which are shrines of Vishnu, and composed several songs in praise of the presiding deities of these places.

It is stated that Ramalinga had some mystic experiences and communication with God during this period, and he relates them in his characteristic moving way.

Once, when he returned late from Tiruvottriyur, he did not want to wake up his brother and sister-in-law. Although he had not taken food, he lay down to sleep on the pial of the open front veranda of the house. He was soon woken up. Beside him stood his sister-in-law with a plate of food. He ate the food and went back to sleep. A little while later he was awakened again, and this time his sister-in-law called him in to dine. In the explanations that followed, it became clear that the first time he was wakened by a vision; and this was confirmed by a second vision of Goddess Vadivudaiya Ammai, with a brass supping plate in her hand. The vision shone before them and promptly disappeared.

Ramalinga has referred to this in three stanzas of a verse, of which the following is one:

That night as I lay on the veranda, cold and tired and hungry,

You, Mother, sweet Fount of Life,

Visited me, asking me, 'Back from

Ottriyur, are you tired?'

And, wonder of Grace, from a blessed

plate out of

Your blessed hand, You blessed me

with blessed food,

O Mother, who reads my aches as if

they are Yours,

O Dancer-King, Accept my

stammering praise!

(Ottriyur is 'Tiruvottriyur,' shorn of the prefix 'Tiru,' which means 'holy.')

On another occasion, Lord Tyagaraja himself is said to have served him food. One day, going without food, as he often did, Ramalinga lay sleeping in the open courtyard of the temple when the priest woke him and served him food. The next morning it transpired that the priest had left Tiruvottriyur two days previously.

His Marriage

His relations and friends tried to arrange his marriage. He 'gave no consent'. It is said that they tried to induce him through an ascetic who, on their request, spoke to him about one's regular duties in life, including those of a 'house-holder' (grahasta), discharging social obligations. Finally he agreed. His wedding is stated to have been performed in 1850 when he was 27. It was a late age for marriage in those days. But there is no authentic record of this date. The bride was the daughter of his sister Unnamulai Ammai, called Dhanammal.

According to the marriage rites, he tied the symbolic, consecrated string (thali) round his bride's neck. With her he spent the nuptial night, reading the pages of Tiruvachaham (Blessed Words) of Saint Manikka Vachahar, his favorite reading. This was repeated on the following nights.

Dhanammal does not figure in his life after this critical period. Nothing is known about her subsequent life.

Editor, Epigraphist and Poet

Ramalinga's years in Madras were marked by great literary activity. Poems and songs flowed from him in profusion. The first 12 years upto 1835 may be described as 'the period of Kandakottam' (the last word meaning 'the temple of Kanda') when he identified himself as a devotee, with God Kandan of that temple, and composed songs in his praise.

The next 22 years until 1858 may be described as 'the period of Tiruvottriyur' when he identified himself, as a devotee, with Lord Tyagaraja (the ascetic aspect of Siva) of that temple, and composed songs in his adoration.

During this period of his life, he edited certain poems of an earlier age and wrote two works in prose.

The first of these was his edition of Ozhivil Odukkam (Primer of Self-Knowledge) of the saint Kannudaya Vallal (1380-1476 A.D.) with the commentary of Tirupporur Chidambara Swamigal; and this was published by Sabapathy Mudaliar in 1851.

The next to be published, again at the request of Sabapathy Mudaliar, was Manumurai Kanda Vachaham (A Tale of Justice) in which Ramalinga gave an expanded version in prose of the story of king Manuchchozhan dispensing justice to a cow, told in the ancient Tamil classic Periya Puranam of Sekkizhar. This was published by Palayam Subbaraya Chettiar in 1854 for the Society for Religious Education.

The third book edited by Ramalinga was Chinmaya Deepikai (Guide to Spirituality) of the poet Mutthaiyya Swamigal of Vrid-dhachalam. This was published by Madurai Mudaliar in 1857.

The second prose-work of Ramalinga, Jivakarunya Ozhukkam (The Law of Compassion for Life) was published only after his passing away.

Bound to Chidambaram

In spite of the homage paid to him in Madras, Ramalinga spent the days mostly outside the city, returning home only at night. He records in a poem, written long after he left Madras:

I feared Madras for its wealth

I feared lest it diminish me. You know,

my Father,

My weary tramps through fields and

hamlets outside the city on roads

of gravel and rubble and

baked earth.

Could written words contain my daily

long exhaustion?

In 1858, at the age of 35, having lived all the years except the first year or two, in Madras, he left the city for good. Accompanied by some of his pupils, he set out on foot to Chidambaram, which still glowed with warmth in his memory. From early years he, born in Marudur, resident successively in Madras, Karunguzhi, Vadalur and Mettukkuppam, took Chidambaram as his eponym, calling himself 'Chidambaram Ramalingam.'

Bound to Chidambaram now, he took his time, visiting sacred shrines on the way, such as Sirhazhi, the birth-place of the great Saivite saint Tirujnana Sambandar. He gave discourses at the temple and composed songs in praise of the deity.

Then he visited Vaithisvaran Koil, here too composing songs and hymns, and finally arrived at Karunguzhi, near his own village, Marudur. His elder brother, Parasurama Pillai, who was living there, died a few days after Ramalinga's arrival. When Ramalinga was about to leave the place for Chidambaram, the revenue officer of the village, named Venkata Reddiar, requested Ramalinga to stay in his house, and Ramalinga continued to stay there. A room was set apart for him in the house; and Venkata Reddiar and his wife Muthiyalu Ammal attended to his needs dutifully for nine years until he left Karunguzhiin 1867.

As in Madras, Ramalinga spent only the nights at home, being out all day, walking with God, worshipping in temples and composing songs. Here his daily tramp was to Chidambaram, to the shrine of the Dancing Siva.

Universal Brotherhood

This spiritual culmination resulted in Ramalinga's founding the Samarasa Veda Sanmarga Sangam or 'Society for Religious Harmony in Universal Self-hood' in 1865. Later, in 1872, he deleted the word Veda (Religion) from the name, and further added two words, Satya ('Truth) and Suddha (Pure) in their appropriate places, thus changing the name to Samarasa Suddha Sanmarga Satya Sangam which means 'Society for Pure Truth in Universal Self- hood', a name transcending religions. This concept is contained even in his explanation of the original name:

The words Samarasa Veda Sanmarga Sangam mean the path pointed to by all religions in common', which is the result of the basic knowledge common to them all. This common knowledge is contained in the fourth path. The four paths are daasamargam, satput ramargam, sahamargam and sanmargam.

According to traditional expositions, daasamargam is the path of approaching God as master, that is, by service to God; satputramargam is the approach to God as father (one considering oneself as the son of God); sahamargam is the approach to God as friend; sanmargam is the approach to God by identifying oneself with him.

This exposition, according to Ramalinga, gives the religious orientation of the paths. He gives the equivalents of these, as oriented to his 'good path of equal vision', by substituting 'Life' for 'God,' as follows:

Daasamargam is to consider all lives as being under one's guardian ship. Satputramaragam is to consider all lives as one's sons. Sahamargam is to consider all lives as one's comrades. Sanmargam is to consider all lives as oneself.

Thus, by one stroke, Ramalinga turned the orientation of the good path from God to the Universe--from an abstract God to the God in Life, from a God apart to the God in the universe. Indeed, the main plank of his path (one should not say 'religion' since he totally eschewed the term) is Jivakarunyam or compassion for life.

The intrinsic nature of the fourth path--the attitude which its adoption automatically evokes in one--is defined by him as consisting of non- killing, forbearance, equanimity, self- restraint, control of the senses, and compassion for life which is the natural quality of the soul.

It is to be noted that he has put non-killing first in the list and that he specifically characterises compassion for life as 'the natural quality of the soul'. This is diametrically opposed to the idea of survival of the fittest which operates in natural evolution. It may be that, in the higher reaches, different laws operate. Ramalinga's path of equal vision also establishes man's relationship with life in the universe as the obverse of his relationship with God.

In Ramalinga's conception, the four prophets of Saivism were exemplars of the four paths, as oriented to God-Appar or Tirunavkkarasar being a servant of God, Jnanasambandar, son of God, Sundarar friend of God and Manickkavachahar realising God within himself as Love.

Compassion for Life

Ramalinga's compassion for life and his logic in the exposition of its place in spiritual life seem to have reached the highest point in this direction attained by man. He lived, moved and had his being in Supreme Grace which, in accordance with his own concept, seems to be an affirmation of his own inward grace. Dandapani Swamigal calls him (in Tamil) 'the Incarnation of Compassion'.

The expression of this profound compassion in his poetry reaches throbbing poignancy. The following verses, thrown together, are taken from different contexts:

Seeing withered corn, my spirit drooped,

Watching the wretch that begged from door to door

unavailing, and hung sank to sleep,

I brooded. At sight of long-racking disease

I shuddered Starvelings, poor, too proud to beg,

and spirit-broken, broke me.

O Last Boon, Shining Lard of Ethereal Space,

When I hear of human creatures starving

or spent with hunger, a fear seizes me,

like afire in the mind, quickly ablaze,

and my body shivers.

Cattle's lowing turned hoarse

Dismayed me.

Bull and beast ill fed

Preyed on me.

When people's voices rose in squabble

A shivering came on me.

When they knocked at the door in frenzy,

It jarred on me.

O Lord, you know, when some one

wailed,

O father, or 'mother' or 'Alas',

The words tore through me

Like an uprooting storm.

O Essence beyond the mind of man,

Final Anchor, my Master,

I, your servant, bound to my kin,

friends, comrades, mother, brothers,

sisters, others, am sore-troubled to see

passing clouds on their faces, You know.

O Father, Splendour of the Cosmic

Stage,

My God, my great. Goal, Need

I tell you

the distress that sears my mind

When, in this distressful world,

Mother, comrades, friends,

People near to me, people next to me,

People removed from me, Suffer, and

I see them suffer, Pangs of hunger,

pain of disease.

Scorching afflictions, Lord,

You do know.

Lord, whose dance is blessing Seed and

of fruit final being

In this passing show of life

Choked by grievous want,

When people greyed and people young,

known and unknown,

recount to me their trials and

tribulations,

My mind trembles and splinters,

Lord, You do know.

He eschewed flesh-eating as something fundamentally cruel and unspiritual, and banned flesh-eaters from his fellowship. He averred that he received this intimation directly from God.

He emphatically repudiated flesh eating. He expressed his horror at the very idea of feeding on animals.

He expressed again and again his horror of killing: He expressed himself against animal sacrifice:

He does away with any possible hostile reaction to his ideas from people by not preaching to them but by placing his agony and his entreaties before God.

Holy Book of Grace

The Sanmarga Sangam (Fellowship of universal Brotherhood) which Ramalinga founded in 1865 in the second phase of his life in Karunguzhi (1858-67) was the seed of his third phase in Vadalur (1867-70). At the same time, the last years in Karunguzhi saw the fruition of his first two phases in the publication of the greater part of his poems by his disciples.

The disciples who took upon themselves this labour of devotion were Velu Mudaliar of Pondicherry, Sivananda Mudaliar of Selvarayapuram, and Ratna Mudaliar of Irrukkam.

During this long-drawn process, Ratna Mudaliar wrote to Ramalinga, in March 1866, to give him permission to print Ramalinga's name as 'Ramalinga Swamigal' (Saint Ramalinga). Ramalinga wrote in reply, 'It goes against my inclination to be paraded as Ramalingaswami. It seems to me that the epithet is pompous and, as such, to be avoided.'

Still keen on paying homage to him, Velayuda Mudaliar, on his own, printed in the book the name that he had coined for his master, namely, Arut-Prakasa-Vallalar (meaning 'Repository of Luminous Grace') called Chidambaram Ramalinga Pillai. When Ramalinga saw the book, he was pained. He consoled himself by saying to his disciples, 'Shall we take the words to mean "Ramalinga who asks Who is the One with Luminous Grace?". (In Tamil the words lend themselves to this interpretation also).

Personal Characteristics

It may be appropriate here to describe some of Ramalinga's personal characteristics.

Tozhuvur Velayuda Mudaliar, in his statement to the Theosophical Society, described Ramalinga in English as follows:

In personal appearance, Ramalinga was a moderately tall,. spare man--so spare indeed as to virtually appear a skeleton--yet withal a strong man, erect in stature, and walking very rapidly; with a face of clear brown complexion, a straight thin nose, very large fiery eyes, and with a look of constant sorrow on his face. Towards the end he let his hair grow long; and what is rather unusual with yogis, he wore shoes. His garments consisted but of two pieces of white cloth. His habits were excessively abstemious. He was known to hardly ever take any rest.

A strict vegetarian, he ate but once in two or three days, and was then satisfied with a few mouthfuls of rice. But when fasting for a period of two or three months at a time, he literally ate nothing, living merely on warm water with a little sugar dissolved in it.

The last achievement of man-- the complete conquest of mind-- was his. He banished mind from him:

You monkey mind, you foolish idiot,

get away!

Stop playing pranks here that you play

with others!

Don't take me for one of them.

If you stay within bounds,

I may let you be

Otherwise, get gone!

No leeway shall I give you, none--

Know me for the true son

of the Lord of the true path.

A Miracle

Ramalinga, in Karunguzhi, did not dwell apart, in a fellowless firmament. His house was by the side of the road, and he was a friend to man. People flocked to him for advice and solace in their troubles.

In Venkata Reddiar's house in Karunguzhi, the mistress of the house, Muthiyalammal herself used to light the lamp in his room and keep near it a mud pot of oil, with which to replenish the lamp. One day, the mouth of the pot having broken, Muthiyalammal wanted to change it. She bought a new pot, filled it with water and let it stand beside the lamp, in order to season it before use. Then she left the house for the next village.

Writing his poems through the night, as he often did, Ramalinga mechanically kept replenishing the lamp with water from the new pot instead of oil from the old. When Muthiyalammal returned the next morning, she found Ramalinga absorbed in writing, and the lamp burning. She discovered his mistake which, without any conscious volition on his part, had resulted in this miracle. So legend has it. In keeping with his habit of recording his experiences, Ramalinga refers to this in a poem, attributing this kind office to God, and not to his own powers.

Appasami Chettiar, one of Ramalinga's admirers, used to come to Karunguzhi from Cuddalore (then called Gudalur) to see his master. Having had his brother cured of an indolent sore on the tongue by the grace of Ramalinga, he placed his hospitality at Ramalinga's service. Ramalinga stayed with him for some months in Cuddalore in 1866.

Widening Mission

After founding the Sanmarga Sangam in 1865, he stayed in Karunguzhi for two years, visiting now and again the places in the vicinity. During one of his visits to Cuddalore, he mentioned to the fellows of the Sangam his intention to build a free eating house which would be open to all, irrespective of caste, creed, country and habits. (In his tract on Compassion he has explicitly stated that these are irrelevant in the exercise of compassion.)

They suggested various places for its location. Finally, Vallalar himself (as Ramalinga is respectfully referred to) chose an open plain, north of Vadalur, a village also called Parvatipuram, 30 k.m. from Chidambaram.

The open space was at the meeting of two highways, one from Madras to Kumbakonam, and the other from Manjakuppam to Vriddhachalam.

On getting to know this, the people owning the land (amounting to 80 kanis or 108 acres) at this site, made a gift of it to him in a deed dated February 2, 1867, bearing the signatures of 40 owners. A temporary building of mud, thatched with reed-grass, was erected.

The feeding of people in the temporary hutment, the construction of permanent structures, the digging of a well, pond and tank for the Hall were started on the same day with a ceremonial opening. A thousand printed invitations were issued to the public. Invitations, written by Ramalinga by hand, were sent to sadhus or ascetics. It is stated that 1,600 people were fed daily for the first three years. The feeding of the hungry and whoever calls there continues today.

The Free Eating House was named Sumnrasa Veda Dharma Salai (Free House of the Good Fellow ship). The word which connotes a free feeding house, in Tamil, is chattiram. Avoiding this with its demeaning associations, he chose the word salai which means 'house'. This name he changed later to Samarasa Suddha Sanmarga Satya Dharma Salai, or Satya Dharma Salai for short.

The same year he founded a school, Sanmarga Bhodini (School for the Fellowship). The unique features of the school were that it was open to all, irrespective of age, boys as well as old people, and that three languages were taught--Tamil, Sanskrit and English, specified in that order. Thozhuvur Velayuda Mudaliar, a reputed scholar in Tamil as well as Sanskrit, and proficient in English, was in charge. The school, however, did not run for long.

In Vadalur

After the opening of the free eating house in 1867, Ramalinga shifted from Karunguzhi to Vadalur. The eating house became his home and the hub of his activities. It became the centre for the work and worship of the Sangam (Brotherhood). Here, in the evenings, he gave discourses to people who flocked from all over the land to see him, listen to him, to have his benediction and his counsel in their troubles and afflictions.

In May 1870, after four years in Vadalur, Ramalinga shifted to Mettukuppam.

He would go daily to Vadalur to inspect and bring to fruition the work that he had commenced there.

He selected an open space of about 50 acres by the eating house. He gave it the name Uttara Gnana Chidambaram (New Chidambaram North). He drew a rough diagram of a temple as he had conceived it, octagonal in shape, and gave it to his disciples, with instructions to erect the temple.

The construction was started in June 1871. He continued to stay in Mettukuppam, visiting Vadalur, supervising the work of the eating house, and the construction of the temple, and giving his guidance when necessary about these projects and also about spiritual matters and codes of conduct to the Brotherhood.

He demanded perfection not only in the construction of the temple but even in the name that he gave it. He did not call it Koil or temple. He called it Sabhai meaning 'Hall' or 'Assembly', the full name being Samarasa Suddha Sanmarga Satya Gnana Sabhai, or in shortened form, Satya Gnana Sabhai (Hall of True Knowledge).

He wanted to eschew anything with a religious connotation. The whole temple was a splendour of symbolism. The Hall of Truth was octagonal in shape. Within it was a twelve-pillared hall, and within it again, a four-pillared hall which housed the symbol of the Supreme Light of Grace on the pedestal of Knowledge.

A consecrated mirror, about four feet in length, was placed to reflect the Light of Supreme Grace, as a model for soul-making. Seven screens of different colours hung, one behind another, representing seven levels of the illusion of tile phenomenal world, which hide the light within man, and which have to be pierced through by knowledge and grace.

Every hail, every gate, every window, every pillar, every arch, every step, north, south, east, west, peripheral, central, every wooden plank and chain, had a symbolic significance.

The temple was opened on January 25, 1872. Ramalinga was not present at the opening. He seemed to be lost in a quest of his own, and yet keen that people should taste of the stupassing joy that he himself had known.

Mode of Worship

The mode of worship in the Sabhai was unique. It was open to all castes, cults, creeds and religion. The only restriction was that meat-eaters should not enter the main Sabhai. They might worship from outside. None was allowed to enter the inner Sabhai for worship. Only for specific functions, like sweeping, cleaning and dusting, lighting the lamp, replenishing the oil, might one among the allotted few enter it. Such were chosen as did not feed their flesh with flesh, would not kill, and had got over their lusts and passion; their caste and creed were of no moment.

There were no accessories for worship, such as flower, fruit, rice, coconut or other offerings, light, incense or music, and no symbol of benediction, such as the handling of consecrated water, sacred ash and the like.

In one of what he calls 'Humble Supplications towards the true path' (Suddha Sanmarga Satya Chiru Vinnappam). he prays:

Lord of all, Supreme Effulgent

Grace!

Grant that henceforth our minds

are not tainted with ritualistic and

other aberrations of creeds and sects,

cultural and other

aberrations of castes

and codes.

Let the awareness of the identity of

the soul in all beings, which

is the prime quest

Of the spiritual seeker, not forsake

us at any time in any degree in

any manner in any place.

Let it ever illuminate and move us.

God of Shining Light we thank

you for your mercy,

We again thank You.

This Sabhai, Hall of Knowledge in Truth, was renovated and reconsecrated by re-dedicated people, headed by the venerable Kripananda Variar on April 24, 1950.

In Mettukuppam, Last Phase

For two years after he moved to Mettukuppam, Ramalinga was involved in the building of the Hall of Truth in Vadalur until it was opened on January 25,1872. Thereafter he steadily curtailed his activities, and started withdrawing into himself. He used to practise yoga, including what is called Brahma-dandika yogam, sitting between two ovens.

In a song he thanks God for helping him to attain the state of yoga in a nazhikai (Tamil unit of time, equivalent to 24 minutes):

Within a nazhikai one evening

You led me to the yogicc state.

By the next morning

You gave me its full fruits.

In common with the siddhas (adepts) of the Tamil land, he held that siddhi, or attainment of divinity with all its connotations, was the purpose of life, not mukti or liberation or release from the cycles of life and death.

While he endorsed the traditional or scriptural conception of mukti, he held that this was not the final goal, being only the penultimate step to siddhi, which is Existing in Divinity or Godhead. According to him, mukti and siddhi are two sides of the same medal, mukti representing the state ripened for Being, and siddhi the Being itself.

It is recorded that one day in October 1870, he became invisible, and remained so for some days. To put his disciples and followers at ease, he forewarned them in one of his regular 'instructions' to them:

Glory to God. Believe that one may be the instrument for good for many. Be assured that you will reap benefit through me. In a few days I shall, by the grace of God, have my body hidden from you. Hold jour patience for a while. Be not afraid. Run the Eating House confidently. Glory to God.

Having sent this notice to Vadalur, he locked himself in his room in Mettukuppam. It is said that for several days the room remained locked, and nothing was seen or heard or known of him until he re-emerged.

It is to be noted that he refers, in his poems and discourses, in contra-distinction to the physical or gross body, to three types of 'pure' body, namely, suddha, pranava and gnana, which may be rendered respectively as psychic or astral (subtle body), devachanic or manas (causal body) and sushuptic or buddhi or arivu in Tamil (spiritual body).

Of the three pure bodies, according to his exposition, the first is free from the limitations of the flesh, such as disease, old age, physiological functions, and it casts no shadow; the second is visible but not graspable; the third is intermittently visible and is beyond time.

In numerous poems Ramalinga refers to his prayers and endeavours to attain the deathless body, and his final success in attaining it along with other super-human powers:

The Body and Face

Of the poems and songs that Ramalinga composed during this period (which were published in 1880, six years after his passing, as the sixth section of Holy Book of Grace) Tiru Uran Adigal says that if we consider the Holy Book as a Body of Knowledge, the sixth section will be the face, the hymn to the Supreme Light the eyes, and the symbolic word (or mantra), Arut Perum jyoti (Supreme Light of Grace) the pupils.

This hymn, composed in ahaval metre, consists of 1596 lines, a dimension not reached in that metre elsewhere in Tamil poetry. We have the date of its composition: April 18, 1872.

The Great Sermon

His most celebrated discourse, his last sermon called The Great Sermon, was delivered by him on October 22, 1873, three months before his passing away, at the hoisting of the flag of the Brotherhood of the Path on Siddhi Vilakam, his house in Mettukuppam.

The flag was symbolic of the channel of mystic power supposed to exist in man, running from the navel to the mid-point between the eyebrows, according to the experience of adepts in yoga. The sermon is revealing in many ways, showing the final development of Ramalinga.

The Passing of Ramalinga

The climax of Ramalinga's dissatisfaction with the running of the Sabhai or Temple was reached in his deciding to close it down in 1873. Within six months of its opening he had issued, on July 18, 1872, written instructions on the manner of running it.

He laid down that worshippers should worship only at the entrance, that people entering the Hall for cleaning it and lighting the lamp should be under 12 or over 72 years of age. He did not find his followers apt.

Closing the Sabhai, he kept the key with him in Siddhi Vilakam. The temple remained closed until four years after his passing away when the fellows of the Brotherhood opened it again and recommenced worshipping there in 1878.

After the closing of the Sabhai came the great sermon at Siddhi Vilakam on October 22, 1873. This marked the end of his outward activities. As if in token of this, in the next month, November 1873, he removed the lighted lamp from his room, and placed it outside.

He told his followers (as has been recorded): 'Without hindrance you may worship here. I shall be closing the door of my room. For some time the Lord will shine in this flame. Avail yourself of this, without wasting time. The song "Thinking, and again thinking of Him", will be suitable for prayer.'

The burning lamp which he placed outside his room in 1873 is still burning today. Thousands are being drawn to that lamp as well as to the other lamp in Vadalur.

After placing the lamp outside, Ramalinga shut himself in his room. Thereafter he used to remain shut in his room for days at a stretch, coming out for a few days, and on those days talking to people and giving discourses.

This went on for three months. He gave an indication of his passing away to the people. He told them (in words that have been recorded) 'I opened my shop. There was no buyer. It will be closed. Now I am in this body. Soon all bodies shall be mine.'

Then came Friday of the eighth lunar asterism, January 30, 1874. As night set in, he called his followers together and said (in words recorded):

I shall remain shut in the room for 10 to 15 days. Don't look into the room and get mystified. If' you do, nothing will show. The Lord will see to it that it is so. He will not reveal me.

At midnight Ramalinga gave his farewell blessings to the people gathered there, exhorting them to follow the path of true knowledge and to seek the grace of the Lord of Supreme Light. Then he turned into the room and shut himself in. Nothing further was seen of him. It is held by his followers that he 'merged into the Supreme Light', that he 'became one with God'.

The passing away of Ramalinga produced a stir and gave rise to diverse rumours until the Government decided to look into the matter. In May 1874, three months after his passing away, Mr. J.H. Garstin, I.C.S., Collector of South Arcot, and Mr. George Banbury, I.C.S., Member of the Board of Revenue, visited Siddhi Vilakam. In their presence the room was opened. It was vacant. They walked round the room. Finding nothing incriminating, they donated 20 rupees for the feeding of the poor which was being carried on there, and left.

Ramalinga has summed up his life as a voyage of spiritual discovery in a song which he wrote in Mettukuppam towards the end of his life:

I crossed the deep. I reached the shore,

I attained

Past the temple door that opened where

the vision glowed.

I gained the grace that ends all pain

I won the Light that lights Intelligence

I gained undying body, powers

mastering

Ills and limits of the flesh, bliss

of soul

Tokens of grace of the great

Dancing Lord.

Ramalinga and Theosophy

Ramalinga did away with all religious doctrines, dogmas, rituals and observances. He declared that his approach was one of true knowledge, the final knowledge and perception of the same quintessential soul in all life as well as in the insentient universe, in varying degrees, a knowledge free of the accretions of religions. This gospel of universal brotherhood and the essential identity of all religions is identical with that of the Theosophical Society, although the vision of Theosophy did not perhaps extend as far as Ramalinga's to embrace the insentient universe, and did not perhaps emphasise the revelatory, soul making and God-making power of compassion for life, as Ramalinga did.

Ramalinga's 'True Knowledge'

The saints tenets chapter might have been titled 'Ramalinga's Religion' but for the fact that the word 'religion', in his later years, was his expressly stated anathema, and he banished all religions from his teachings, retaining only their core, which he called 'true knowledge' and which he realised as Supreme light. Likewise, the Upanishads declare that soul-realisation is born of the knowledge of the soul (Atma-vidya).

Ramalinga's conception of the Supreme light can thus be traced to the Gayatri of Rg Veda. The Gayatri Mantra (Gayatri spiritual formula or watch-word), in its span of 24 syllables is generally recognised as the quintessence of Vedic teaching Within 24 syllables it embodies a lofty spiritual quest which will suffice for the spiritual development of any intellectual man through his lifetime.